Sports Gaming

How Close Are Sports Games to Reaching their Graphical Peak?

If you grew up during the explosion of video games as entertainment in the ‘80s and ‘90s, you’ll likely remember the famed console wars. This series of battles between Nintendo, Sega, and later, Sony, would spark an exciting period in which the next best thing was always around the corner. Games rarely felt or looked the same from year to year, console to console.

Sports games have always been an integral part of this ride and are arguably the best gauge we have for evaluating the progress that our beloved genre has made and, possibly, could make.

Using that gauge, we come to a simultaneously important and arbitrary question: how close are we to seeing the “peak” of sports gaming realism? To be more specific, at what point do we stop being able to discern what, if any, progress has been made at all? What will that peak look like?

Phase 1: Early Growth

Gameplay is the life blood of any sports title, and what ultimately keeps us hitting that power button, but graphics are the exterior neon sign that gets us in the door, especially as younger gamers. There was Sega’s blast processing, Nintendo’s Super FX chip, Sony’s discs and Microsoft’s PC-like structure that all had the same goal in mind: have us picking up our jaw and tongue from the floor like 1994’s ‘The Mask’ while nagging your parent of choice about the new true love in your life.

In some instances, it didn’t even matter what games were launching with the console, all that mattered was the promise that this time things would be even more real than before. And for many console cycles, that is precisely what happened, sometimes within a cycle itself. As multi-platform gaming became more common, so too did the comparisons between which current console carried the “best” version of a title. The judge, jury and executioner of this question was graphics.

The opening statements were the bits the console boasted, and the cross examination saw us performing the eye test in magazines or craning our necks at demo kiosks in the electronics section. The verdict could be harsh, as you envy the friend with the “correct” console for this particular title.

Early examples would see NBA Live 95 featuring players jogging to half court during introductions on Genesis, while SNES players got their starters via text over a dimmed screen. When the game began, the difference was clear. From the shadow of the backboard to the popping colors of the uniforms, it was apparent that although a sports game commercial may lump all the different ways to play together, there was likely a “best” way to play. As time went on, these differences within the console cycle itself began to blur.

NBA Live 95 – Genesis

NBA Live 95 – SNES

Phase 2: Accelerating Progress

Moore’s Law, a concept introduced by Intel’s co-founder Gordon Moore in 1965, states that computing power and capability is roughly doubled every 18 months. The world of gaming followed this same pattern from generation to generation, with perhaps the most remarkable leap materializing in the form of disc-based games becoming the norm, and the arrival of Sega’s Dreamcast, Sony’s PlayStation 2, and newcomer Microsoft’s Xbox.

Comparing Madden 2000 on the previous generation with Madden 2001 on the newest generation was the equivalent of finding your glasses in the morning and realizing you couldn’t see a thing before that moment. Gone were the blocky forms that would sometimes chuck a football-like object, and in their place were…humans? The lines around players curved into more pure representations, accentuated by their casual sway as they stood in the huddle. The on-field art, the stripes on the referees’ shirts, and even the players’ gloves and elbow pads were suddenly realized with such confidence that the camera was willing to zoom in for a closer look.

Madden 2000 – PS1

Madden 2001 – PS2

As important as the hardware was, so too was understanding the limits of the hardware for developers. That same Madden 2001 PS2 title, compared to the final iteration on the console in Madden 12 (seriously the PS2 era lasted that long, isn’t that wild?), highlights what developers can and cannot do when it comes to pushing graphical presentation. When examining the player models themselves, they remained largely unchanged in many respects.

A similar dynamic is viewed when comparing NHL 2001 to NHL 09. If you were to sit down not knowing which of that generation’s hockey games you were about to hit the ice on, would you be able to tell simply from the graphical quality of the players? If you can tell, would this seem a reasonable jump after eight years?

NHL 09 – PS2

NHL 2001 – PS2

And yet, when Madden 12 and NHL 09 are compared to their predecessors in motion, it is completely apparent that the newer title “looks” better. This leads to an interesting question: when we as sports gamers look to a new title and say, look what they did with the graphics, what is it we’re actually talking about? If a game at the end of a console’s cycle is not that far off from the beginning, what is the neon light that’s flashing this time?

A simple answer lies in how those assets are presented. During the PS2 generation, there appeared to be a shift from pure graphical enhancement to changes in presentation being the placeholder until the next great leap toward full realism that the next console always promised. While the faces were sharpened nominally, or the animations made crisper from launch day on, the true upgrade came in seeing those assets gain new elements around them.

Madden 12 did manage to clearly be the more advanced graphically due to the addition of these other assets. Weather patterns, adjusted lighting and a more dynamic scoreboard accentuated the presentation. In NHL 09, the ice was more believable, and the players’ skating motion appeared less stiff. These and other features came together to make the titles feel more complete, and thus to our minds, more real even if the very uniforms they wore were not any more noticeably detailed than before.

Later on, as face scanning technology became more polished, this too would play a huge part in how what we were playing represented its true counterpart. The addition of accurate tattoos, hair and even skin textures took their part in the formula, assisting in pressing the genre further toward indistinguishable territory. However, these features too were bound by the limits of the current console, and so these improvements in scanning may have looked much the same in Madden 2001 as they did in Madden 12.

By this point, we were conditioned to the way of Moore’s Law, that the arrival of the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 would bring about the next great leap in realism. And once again, we were not disappointed. If the transition from PS1/N64 to PS2/Dreamcast/Xbox was like finding your glasses in the morning, then the debut of the Xbox 360, and later the PlayStation 3, was like receiving a new superpower granting hawk-like vision.

Phase 3: Clarity

High-definition was one of the biggest game-changers in the evolution of realism, a change so radical it required an entire change of equipment to enter the bold new world of sharpness. The day I went to purchase my PS3 on launch day, a buddy helped me double-lift an HDTV, as well. The neon sign was flashing that a new dawn was here, and we were not going to miss the train.

And what a ride that train was. FIFA 06 and FIFA 06: Road to the World Cup were released in the same window, and yet the latter makes the former look like a poor approximation of what sports gaming was supposed to look like all along. Once our eyes had adjusted to the sudden epiphany of clarity on-screen, the enhancements were apparent. Did the soccer ball actually spin before? Even if it did, it would have been impossible to notice without some effort. But there it was now, in its vibrant patterns, telegraphing the coming bend into the net.

The models showed true definition in their faces, carrying through to their expressions of triumph and pain. The kits billowed with movement, hair carried more definition and texture, the pitch colors popped, and shadows crisscrossed on the ground with the pattern of the unseen rafters above. If the window-dressing of additional assets a generation before was the carving of a model for the future of sports titles, then the arrival of HD was the transformation of those assets into a real boy.

Phase 4: Did Someone Pull The Brakes?

But were we nearing the end of the fairy tale? How could that be, especially if Gordon Moore had promised us otherwise, and the consoles we love had delivered time and time again? After all, there was a massive leap forward in graphical fidelity on the Xbox 360 and PS3 with titles like Gran Turismo, Forza, NBA 2K, Madden, Tiger Woods PGA Tour, WWE Smackdown vs. Raw and others.

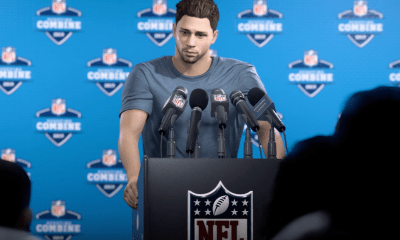

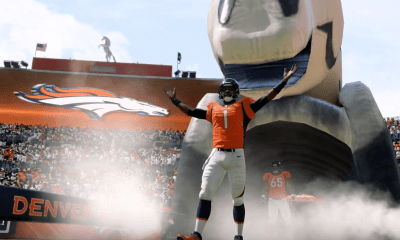

This new and unfamiliar reality hit gamers with the release of the current generation of consoles, the Xbox One and PlayStation 4. For the first time, instead of a new console enticing a game of “see who can point out the most new things,” gamers were playing a sort of Where’s Waldo? when searching for the apparent upgrades.

NBA 2K14 – PS3

NBA 2K14 – PS4

To be sure, they were and are there. A comparison of NBA 2K14 for PS3 and PS4 reveals greater definition in player expressions, an improved reflective court to the lights above it, uniforms that pop a bit more, and better-defined audience members. But perhaps this is itself an indication that change had come, that these improvements for the first time were not game changers, but rather tweaks to things that already existed.

And while it cannot be said that sports games have added all things that could possibly exist in their particular form of competition, it could be argued that the foundation is as set as it ever will be. While I would for one welcome the addition of baseball stoppage due to a squirrel on the field, the truth is that we have exited the age of “additional assets” and seem to have entered a fourth, and possibly final, stage.

This stage is an era of polish. It is a time of improving the accuracy of player movement and making sure that the newest hairstyles are included. It is a time of arena lighting tweaks, and piles of branded gear. Are we about to reach the peak of graphics in sports games? Have we already arrived? What does the peak look like? Does it mean that the virtual and real worlds are completely indistinguishable, or perhaps simply that all elements possible in a competition, from sweat to number font, are present?

If we’re to look at this from a purely computing standpoint, there are indications that Moore’s Law is slowing down. However, this could well be a temporarily dormant period for the progress of technology, as the continual shrinking of processing chips reaches its limit. Other methods could be on the horizon, from what comes after silicon to quantum computing, but none of these are on the immediate radar.

In the meantime, will sports gamers continue to care if the neon light finally burns out completely? There are some that will be satisfied with the gameplay they have come to love, but if that sign that brought us here is missing, where do the next sports gamers find their beacon? Is it possible that as graphical improvements slow, so too do sports games?

And what of the possibility that current technology methods have yet to reach their full potential? Every console cycle brings with it increased costs for developers and hardware manufacturers, with even current consoles not housing the most advanced components available. While this keeps the cost of units consumer-friendly, does that also make it impossible to reach the true apex of graphics in gaming, whatever that looks like?

Whatever the path forward, the nature of sports gaming promises that we will be at the forefront of this answer. Developers across a range of sports will continue to push the limits of hardware and find new ways to keep the neon flowing just a bit longer. We then are the only true year-to-year tracker of the progress gaming graphics make. We will know how close the industry is to tricking a friend or family member into watching an entire game of Madden and telling the folks at the water cooler tomorrow morning that they just watched an amazing NFL broadcast last night.